Tai Long Wan -- Tales from a vanishing village

by Keith Addison

Tai Long Wan village, Shek Pik, Lantau, Hong Kong, 1983-85

|

Stories by Keith Addison |

| Tai Long Wan -- Tales from a vanishing village Introduction |

|

Tea money |

|

Back to basics |

|

Forbidden fruit |

|

A place where nothing happens |

|

No sugar |

|

Treasure in a bowl of porridge |

|

Hong Kong and Southeast Asia -- Journalist follows his nose |

| Nutrient Starved Soils Lead To Nutrient Starved People |

|

Cecil Rajendra A Third World Poet and His Works |

|

Leave the farmers alone Book review of "Indigenous Agricultural Revolution -- Ecology and Food Production in West Africa", by Paul Richards |

|

A timeless art Some of the finest objects ever made |

|

Health hazards dog progress in electronics sector The dark side of electronics -- what happens to the health of workers on the production line |

|

Mo man tai ('No problem') -- "Write whatever you like" -- a weekly column in Hong Kong Life magazine Oct. 1994-Jan. 1996 |

|

Swag bag Death of a Toyota |

|

Zebra Crossing -- On the wrong side of South Africa's racial divide.

|

|

Curriculum Vitae |

|

|

Food comes first, and the villagers have got their priorities straight. They don't say "Hello," they say: "Have you eaten yet?" They always eat at the same times, so there's no surprise in the answer.

Until we arrived. We were always busy and usually ate when we had the time, unless we got hungry first, and suddenly the meaningless question gained a whole new level of interest: "What? You haven't eaten yet?" They couldn't believe the weird times we had or hadn't eaten, it caused a lot of talk.

Granny Fung -- Drawing by Christine Thery |

"No," I said, but Christine, in the same breath, said "Yes." I stared at her in surprise. (I'd just finished a long telephone conversation and she'd got hungry and had some lunch.)

Granny Fung couldn't believe it, it was the funniest thing she'd ever heard -- she shrieked with laughter: "You've eaten," she spluttered, "but he hasn't!" And she went off, still cackling, snack forgotten, to tell the neighbours.

"That made her day," said Christine, laughing.

"But I wanted to talk to her," I said. "Her lettuce crop is ready and we want some."

So we followed the old woman and found her at the Widow Fung's house, both of them shrieking with laughter. And of course the Widow Fung had to ask the question too, and got the same answers. When they'd quietened down a bit we asked Granny Fung if we could have a couple of her lettuces.

"Sure," she said. "Come down to the field and I'll get some for you."

And the Widow Fung, in an untypical fit of generosity, gave us some of her baak choi and choi sum, fresh-picked that morning. "Very sweet!" she said.

Chinese white cabbage -- baak choi (Geoffrey Herklots) |

All the villagers seemed able to get that perfect flow in their fields without even trying, even though they remade the beds several times a year.

We'd tried it in one field after making our first raised beds and paths: the water flowed halfway down the first path and stopped, puddled, trickled on a bit further, stopped again, backed up...

Flowering Chinese cabbage -- choi sum (Geoffrey Herklots) |

We reached the Fungs' lettuce bed. "How many would you like?" she asked.

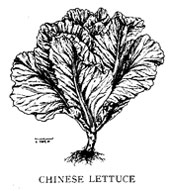

"Two please," said Christine, so she pulled up two nice ones and gave them to Christine. Chinese lettuce is loose-leafed and the villagers pull them up roots and all rather than cutting them like baak choi, and this was why we wanted them -- we wanted to regrow them.

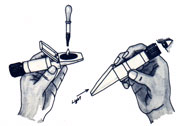

We thanked her and took the lettuces home, along with the Widow Fung's choi. In the kitchen, we sliced the lettuce leaves off just above the root, and Christine tested them with our new refractometer while I took the two roots to the chicken shed where we made our compost and replanted them in pure earthworm castings, which is about the best soil there is.

Well, so what, who needs more sugar anyway? For one thing, this is real sugar, not that whiter-than-white poison in the sugar bowl, and for another, a plant's mineral and protein content, and protein quality, are directly related to the sugar content in the sap. So the refractometer is a reliable, quick and cheap quality test. It's also been shown that plants with high sugar levels are much less prone to pest attack -- healthy, well-fed plants have good resistance, like healthy, well-fed people.

Standard sugar levels have been worked out: for lettuce, 4% is poor, 6% average, 8% good and 10% is excellent. (See list below.)

Granny Fung's lettuce measured 1.5%, worse than poor -- empty, hardly worth eating. The Widow Fung's baak choi also measured 1.5%, and the choi sum 2% -- not "very sweet" after all.

Granny Fung's lettuce measured 1.5%, worse than poor -- empty, hardly worth eating. The Widow Fung's baak choi also measured 1.5%, and the choi sum 2% -- not "very sweet" after all.That made us sad -- they worked so hard, for such poor results. But we weren't very surprised, though we hadn't expected it to be quite so poor. The soil was poor, and the villagers' soil maintenance methods were also poor.

Old man Fung and his old wife were fairly typical. They were well into their 70s and they were alone: their six children had left the village, and they lacked the strength and the labour to continue with the old methods. Weeds and crop wastes were once dug into the soil, but now they were burnt to ash, and the ash used as a fertilizer.

They'd always burnt rubbish and used the ash, but now that they burnt everything, no organic matter was being returned to the soil. They'd sold their cattle and pigs long ago when they gave up growing rice, and now they only had a few chickens, so they had no manure, except their own, which they diluted and fermented in big earthenware urns before diluting it further and sprinkling it under the plants, which supplied some nutrients, but not organic matter.

The ash and nightsoil wasn't enough, so they made up for it with chemical fertilizers, which still wasn't enough, and did nothing at all for the thin, over-ashed, undernourished soil. So they had pest problems -- such weak plants are a beacon for pests -- and they also had weed problems, since nature insists on repairing such poor soils by growing weeds in them.

We reckoned that the villagers could cut a lot of labour by making permanent, deep beds and composting the crop wastes rather than burning them, to build up the organic matter in the soil again and give it some life. This would also cut the weed and pest problems, saving more labour and the expense of fertilizers and pesticides. The earthworm composting system we were using, apart from being quite simple and producing a high-quality product, also produced a lot of excess worms which made fine chicken-feed -- the village chickens were also in poor shape, though the feed bills were high (higher than the value of the eggs).

We hoped this lettuce test would show us whether we were on the right track or not.

Chinese lettuce (Geoffrey Herklots) |

So there was nothing wrong with the lettuce that a good soil couldn't put right. We went ahead with the composting work and the no-dig beds.

We also tested as many different lettuces as we could find, from other fields, from other villages, from rural and city markets, from supermarkets. A lettuce from China measured 2%, a HK$9.50 import from California, 2.5%, a luxury lettuce flown in from Paris, costing $22, also measured 2%. Nowhere could we find a lettuce that even rated "poor".

In fact we could hardly find any vegetables that had anything in them: baak choi, 1.5%, choi sum 3%, Californian celery 3%, Australian tomatoes 4%, US tomatoes 4.5%, Chinese bell peppers 4%, local cauliflower 3.5%, American cabbage 4.5% -- all poor or worse.

Broccoli, carrots, spring onions and sweet potatoes tended to be somewhat better, but not reliably, and nothing was "excellent". Nothing but bad news: nearly all available vegetables are very poor quality.

Healthy salads

Lettuce is good for you. It's the basic salad ingredient, it's recommended for its high calcium content to people with an intolerance for dairy products.

According to a textbook on nutrition, 100 grams of lettuce contains, among many other things, 77mg calcium, 30mg phosphorus, 2.3mg iron and 10mg vitamin C.

An average-sized lettuce will give you half your daily requirement of calcium, a fifth of your phosphorus, all your iron, and a third of your vitamin C. (Though actually the vitamin C level plunges to about half within an hour or two of picking.)

But another textbook gives different values: 44 per cent less calcium, 40 per cent more phosphorus, 74 per cent less iron and 20 per cent less vitamin C. Two other books give calcium values for lettuce only a third as high as the first book.

There are other, more extreme, variations: the calcium value for cabbage in the second book is 224 times higher than in the first book.

Severe pest damage to a village crop of baak choi |

There was no visible difference, no way of choosing the good tomatoes.

So much for the balanced diet. Lettuces are healthy food? -- which particular lettuce is that?

What matters is where it's grown, and how: if it's grown in dead soil with harsh chemical salts as a substitute for natural fertility it's not going to contain much of anything worth eating -- it won't be healthy and eating it won't make you healthy.

But even good soil is no guarantee of quality. A lot of modern food plant varieties are hardly worth eating no matter how they're grown, because they're engineered that way: they lack the ability to take up important nutrients even when the soil has them.

Corn (maize) is a useful plant: it has a good protein-carbohydrate balance and a good spread of minerals -- if it's old-fashioned "open-pollinated" corn, that is. But if it's a modern hybrid variety it will probably be severely short on vital trace elements, and some may be lacking altogether.

Though they require only minute doses, plants need at least 40 different trace elements (iron, manganese, boron, zinc, copper, cobalt, molybdenum, etc.) without which their metabolic processes, particularly their enzyme systems, can't function properly -- and neither can ours.

Simply put, hybrids are crosses between different strains that have been inbred (forced to self-fertilise); the result is a plant that puts the energy that should go towards reproducing itself into extra growth instead. So hybrids are big yielders.

But when a natural, open-pollinated variety of corn was tested against 4,000 hybrid samples grown across 10 states in the US, the hybrids had an average of only 20 per cent of the nutrients of the open-pollinated corn. All the hybrids tested were short on trace minerals, and none contained any cobalt, which is the core element of vitamin B12.

We need cobalt to form haemoglobin in the blood, and to prevent nerve degeneration. Vitamin B12 deficiency can cause weakness, permanent nerve damage, pain in the extremities, liver enlargement, skin problems, and more.

But it's quantity that pays, and hybrids account for 98 per cent of the US corn crop today. This is mostly field corn used for stock feed (which doesn't say much for the quality of the meat) but the same thing applies to sweetcorn. And it's not just in the US -- natural corn is now universally rare.

In theory, hybrids are not necessarily all bad -- it depends on which particular traits they were developed for. In practise though, they are generally developed for bulk. Nutritional value is ignored.

It is not that open-pollinated corn can't compete. What it lacks in bulk it makes up for in protein content, and it's been found that livestock eat less of it and thrive better. And, when properly grown, well supplied with trace minerals and with its enzyme systems functioning properly, it can, like all healthy creatures, defend itself against pests and disease and doesn't need huge and repeated doses of powerful poisons to survive.

Commercial crops of onions, celery, carrots, cabbage, cauliflower, broccoli, brussels sprouts, tomatoes, cucumbers, squashes, pumpkins, sweetmelons, bell peppers, aubergines, and particularly wheat and rice are now increasingly hybridized -- and likely to be nutritionally empty.

Whether hybrids or not, virtually all commercially grown vegetables are heavily chemicalized. Reliance on chemical fertilizers has led to a massive decline of soil fertility.

Sick soils produce sick plants, and today's pest-prone crops are sprayed up to 40 times from seed to harvest. Many of the pesticides are fat-soluble, which means they can penetrate the plant tissue and cannot be washed off -- they're inside the plant. (It's estimated that 64% of the heavy doses of pesticides applied to commercial wheat crops survive in the baked loaf of bread.)

So your healthy salad almost certainly lacks nutrients -- but not poisons.

(1984)

Refractometer readings

Plants

Poor

Average

Good

Excellent

Alfalfa

4

8

16

22

Apples

6

10

14

18

Asparagus

2

4

6

8

Bananas

8

10

12

14

Beets

6

8

10

12

Bell Peppers

4

6

8

12

Broccoli

6

8

10

12

Cabbage

6

8

10

12

Carrots

4

6

12

18

Cantaloupe

8

12

14

16

Cauliflower

4

6

8

10

Celery

4

6

10

12

Cherries

6

8

14

16

Corn stalks

4

8

14

20

Corn (Field)

6

10

14

18

Corn (Sweet)

6

10

18

24

Endive

4

6

8

10

Peas

8

10

12

14

Grains

6

10

14

18

Grapes

8

12

16

20

Grapefruit

6

10

14

18

Green Beans

4

6

8

10

Honeydew

8

10

12

14

Hot Peppers

4

6

8

10

Kohlrabi

6

8

10

12

Lemons

4

6

8

12

Lettuce

4

6

8

10

Limes

4

6

10

12

Onions

4

6

8

10

Oranges

6

10

16

20

Papayas

6

10

18

22

Parsley

4

6

8

10

Peaches

6

10

14

18

Peanuts

4

6

8

10

Pears

6

10

12

14

Pineapples

12

14

20

22

Potatoes

3

4

6

7

Raspberries

6

8

12

14

Rice

4

8

12

16

Sorghum

6

10

22

30

Soybeans

4

8

12

16

Squash

6

8

12

14

Strawberries

6

10

14

16

Sweet potatoes

6

8

10

14

Tomatoes

4

6

8

12

Turnips

4

6

8

10

Watermelons

8

12

14

16