A Third World Poet and His Works

by Keith Addison

Published in South China Morning Post, September 19, 1982, and Bangkok Post, December 5, 1982

|

|

| Strength underpinned with skill by Keith Addison Published in Far Eastern Economic Review, June 23 1983, and Sunday Star, Malaysia, June 26 1983 Full story |

|

Books by Cecil Rajendra Full list |

|

The Animal & Insect Act Finally, in order to ensure absolute national security they passed the Animal & Insect Emergency Control & Discipline Act. Under this new Act, buffaloes cows and goats were prohibited from grazing in herds of more than three. Neither could birds flock, nor bees swarm ..... This constituted unlawful assembly. As they had not obtained prior planning permission, mud-wasps and swallows were issued with summary Notices to Quit. Their homes were declared subversive extensions to private property. Monkeys and mynahs were warned to stop relaying their noisy morning orisons until an official Broadcasting Licence was issued by the appropriate Ministry. Unmonitored publications & broadcasts posed the gravest threats in times of a National Emergency. Similarly, woodpeckers had to stop tapping their morse- code messages from coconut tree-top to chempaka tree. All messages were subject to a thorough pre-scrutiny by the relevant authorities. Java sparrows were arrested in droves for rumour-mongering. Cats (suspected of conspiracy) had to be indoors by 9 o'clock Cicadas and crickets received notification to turn their amp- lifiers down. Ducks could not quack nor turkeys gobble during restricted hours. Need I say, all dogs -- alsatians, dachshunds, terriers, pointers and even little chihuahuas -- were muzzled. In the interests of security penguins and zebras were ordered to discard their non-regulation uniforms. The deer had to surrender their dangerous antlers. Tigers and all carnivores with retracted claws were sent directly to prison for concealing lethal weapons. And by virtue of Article Four, paragraph 2(b) sub-Subsection sixteen, under no circumstances were elephants allowed to break wind between the hours of six and six. Their farts could easily be interpreted as gunshot. Might spark off a riot ..... A month after the Act was properly gazetted the birds and insects started migrating south the animals went north and an eerie silence handcuffed the forests. There was now Total Security. -- Cecil Rajendra, Refugees & Other Despairs, 1980 |

|

Hothouse Anachronisms "Slash and Burn Vandals" they branded us in treatise, journal, book and exegesis. And yes, we confess we were guilty of felling trees to meet our daily needs: fuel to simmer our gruel, on cold nights firewood to keep us warm. . . . But vandals we never were, we never took any more than absolute essentials. Never! Yet, "Slash and Burn Vandals" they branded us in treatise after treatise, book, journal, exegesis. . . . the well-intentioned environmentalists in the metropolis. Never once questioning the hectare upon hectare of our forests filched to feed those voracious presses that churned out magazines, journals, books, treatises, papers and exegeses that condemned us as savages-- unthinking, unfeeling "Slash & Burn Vandals." Cecil Rajendra Poetry from The Literary Review: An International Journal of Contemporary Writing http://www.webdelsol.com/ tlr/tlrsu-cr.htm |

|

Stories by Keith Addison |

| Tai Long Wan -- Tales from a vanishing village Introduction |

|

Tea money |

|

Back to basics |

|

Forbidden fruit |

|

A place where nothing happens |

|

No sugar |

|

Treasure in a bowl of porridge |

|

Hong Kong and Southeast Asia -- Journalist follows his nose |

| Nutrient Starved Soils Lead To Nutrient Starved People |

|

Cecil Rajendra A Third World Poet and His Works |

|

Leave the farmers alone Book review of "Indigenous Agricultural Revolution -- Ecology and Food Production in West Africa", by Paul Richards |

|

A timeless art Some of the finest objects ever made |

|

Health hazards dog progress in electronics sector The dark side of electronics -- what happens to the health of workers on the production line |

|

Mo man tai ('No problem') -- "Write whatever you like" -- a weekly column in Hong Kong Life magazine Oct. 1994-Jan. 1996 |

|

Swag bag Death of a Toyota |

|

Zebra Crossing -- On the wrong side of South Africa's racial divide.

|

|

Curriculum Vitae |

|

|

Malaysian poet Cecil Rajendra's poems turn up in the most odd places: at a church-sponsored conference on the evils of tourism, in a Black South African liberation movement's newsletter, in a mass-circulation Japanese daily paper, in a Filipino law professor's human rights lectures, in a geography textbook for British schoolchildren, in a Bengali magazine, in a book about militarism, in a Time magazine cover story, in a Penang taxi driver's glove compartment -- but seldom in literary journals.

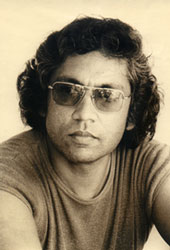

Rajendra: "Almost every aspect of our lives here is circumscribed by some piece of legislation or other." -- Photograph Christine Thery |

"My poems tend to be more a part of Third World studies than literature studies," Rajendra says. "They find themselves in all sorts of places, and I am most pleased about it."

He is genuinely not interested in literary acclaim, nor abuse, though he has received plenty of both. Rajendra judges his work strictly in terms of its effectiveness in awakening people to the burning social issues that afflict Malaysia and the Third World generally -- oppression, injustice and exploitation, corruption and greed, want, hunger and poverty, ecological ruin.

His poetry is part of a total commitment. A lawyer by profession, he handles mainly pro bono cases where a principle of justice is involved, defending factory workers who find themselves on the wrong side of the country's highly oppressive labour laws, taking drugs cases involving youths from fishing villages shattered by ill-considered tourism projects, representing peasants denied justice because once in the witness box or dock they are struck dumb by the augustness of the proceedings, the belittling effect of the legal stage props, the theatrical pomposity of the official fancy dress.

Though he wins cases and obtains some measure of justice, he sees law and justice as two different things in Malaysia: "There's no question of practising law here, it's almost a farce.

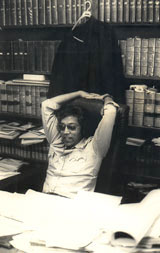

Rajendra the lawyer: "I often have to suspend my sense of reality when I enter court." -- Photograph Christine Thery |

After a succession of setbacks, he has set up a free legal advice centre in a depressed rural area in Penang, serving needy people who would normally have no access to legal representation.

He has also considered giving up law altogether and taking up writing full-time, perhaps as a journalist at The Star, a national daily tabloid which publishes his controversial weekly column on the arts scene, as well as many of his poems.

"The Star has a readership of about 300,000," he said. "That's fantastic for a poet. It is one of the few papers here that is prepared to take a few risks. I've managed to have a lot of poems published through them that were very critical of some of the things that go on here, and the feedback I've been getting has been most encouraging.

"I wrote a poem called 'The Animal & Insect Act' about some of our repressive laws -- almost every aspect of our life here is circumscribed by some piece of legislation or other.

"People told me I'd never be able to publish it in this country, it was much too explosive, and at first it was circulated on roneoed sheets. Then I talked to the editor of The Star about the poem. He agreed to publish it, and I was amazed at the impact it had.

"For instance, one day I caught a taxi to Georgetown from my home on the outskirts of the city. We set off, and the driver started chatting to me. He asked if I was Cecil Rajendra. I said I was, and he said, 'I liked that poem that you wrote very much.'

"And he opened his glove compartment and took out a cutting of 'Animal & Insect Act' from The Star, saying, 'It's about time people spoke up about these things.'

"I was astonished -- he was a semi-literate guy, a taxi driver, how remote poetry must be from him. Yet he cut it out and kept it in his glove compartment. I was more flattered by this than by anything else. You would never get such a response in Europe. I lived in London for 13 years, and I regularly go back there; my readings there draw a lot of attention, but in terms of the real, immediate effect you can have, this place is far more direct."

"Animal & Insect Act" is one of Rajendra's most interesting poems. He followed up its publication in The Star by including it in "Refugees & Other Despairs", his fifth poetry collection, published in Singapore by Choice Books.

It has since travelled far: it was first heard in the US when Filipino law lecturer Dr Cesar Espiritu read it at a human rights seminar in Washington; he now uses it to illustrate all his human rights lectures, and the poem has since been published in the US, as well as in West Germany, Spain, South Africa and Japan, where it was included in a book on militarism in Southeast Asia entitled "People Against Domination."

Rajendra read it at a poetry recital during the Third World Book Fair held in London in April and was invited to read it on the BBC, which he did soon afterwards.

Echo from the past

The poem has an almost weird historical correspondence of which Rajendra himself was unaware. His angry ridiculing of modern security laws by applying them to animals is a strange echo of a similar anger finding the same expression, by a Malay social commentator writing 150 years ago.

Abdullah bin Abdul Kadir Munsi, research assistant of the famous Sir Stamford Raffles of Singapore, was appalled to learn that in the Malay state of Trengganu people were forbidden to use an umbrella, wear shoes or dress in yellow in the vicinity of the ruler's palace.

"Why aren't the birds prohibited from flying over the palace, or the mosquitoes prohibited from sucking the royal blood, or the lice from setting on the royal pillow or elephants from trumpeting in front of the palace?" he demanded, while real evils such as drug-taking, disease, poverty, ignorance and squalor were ignored.

This mirror-image from the past is significant because, though Rajendra has deep roots in Malaysia, he is often accused of being an expatriate at heart by the academics and formalists of the local literary establishment, who tend to see the social commitment in his writing as artistically gross, a pollution of literature.

"Dynamic" was how a reviewer of Britain's Times Literary Supplement judged Rajendra's work. "The whole experience was a complete, if unconscious, refutation of the academic and disengaged approach."

Certainly his inspiration has been more international than local: his technique has been influenced by the directness of the Japanese haiku poets, his thinking by such men as Amilcar Cabral, Pablo Neruda, Franz Fanon, Walter Rodney, Martin Luther King, Malcolm X, Wilfred Owen, Dennis Brutus.

He is a Third World poet and his work finds relevance wherever men are poor and oppressed, exploited and robbed of their heritage. But it is with Malaysia that he is chiefly concerned, and about Malaysia for Malaysians that he writes.

"Faults in another / that would not matter / in our loved ones / assume / cataclysmic proportions / and if i did not care / i would not dare / chart / your many imperfections" he writes in "To my country".

But his Malaysian critics, both literary and political, do not see it that way, and he has been subjected to considerable pressure. So have the editors of The Star, and the publishers of "Refugees & Other Despairs", who responded by quietly withdrawing the book from circulation. Rajendra now plans to have it reprinted elsewhere.

"Faults in another / that would not matter /

in our loved ones / assume / cataclysmic proportions /

and if i did not care / i would not dare /

chart / your many imperfections"

He has found the wide relevance of his work useful as well as gratifying. He claims that Heinemann (Asia), who published "Bones & Feathers", his fourth poetry collection, would never have accepted some of the poems in the book had he not been deliberately misleading about their origins. "My particular concern in writing these articles for The Star is culture, its role in society, how one can use culture to make people more conscious. Local artists have no confidence in their own culture. We take promising young people who produce work that is relevant and in context with the society they're living in, and send them overseas to study.

Rajendra's address, "The Higher Duty of a Writer in a Developing Society", sparked off another storm: In an Asia ravaged by war, famine, disease, malnutrition, military repression, economic exploitation and ecological ruin he said it was indefensible not to take sides, not to be concerned with social justice and human rights.

"The Political Prisoner", dedicated to Nelson Mandela, jailed leader of South Africa's African National Congress, "The Fan", a chilling poem about an interrogation, dedicated to exiled South African activist and poet Dennis Brutus, one of Rajendra's early mentors, and "Salisbury -- City of Night", with its "armies of sleepwalkers", were in fact all written about Asia.

Conversely, poems written about other countries have been taken to refer to Malaysia.

"When the tourists flew in", also from "Bones & Feathers", was written after a visit to Trinidad, and also partly about Haiti, where shanty towns were preserved as tourist attractions -- "chic eyesores", as the poem has it.

Fishing off Tanjung Bunga Beach in Penang...

Yet the poem fits Malaysia almost perfectly, and especially Penang, where strips of beach hotels have displaced and disrupted fishing villages (including the one Rajendra was born and raised in); fishermen have indeed become waiters, there is a rash of escort agencies where before there were none; beaches are reserved for the exclusive use of hotel guests, and recently the residents of a rural village were outraged when tourist buses began arriving, bringing hordes of foreigners to gape at them.

This is perhaps Rajendra's most widely travelled poem. It was originally published in the Caribbean, and, apart from in "Bones & Feathers", it has since been published in Japan, the Philippines, Bangladesh and several other Third World countries.

... But now the beach is cut off from the fishing village by a new road.

Rajendra read it at a conference on tourism held in Manila at the end of 1980, where it was picked up by a regional news weekly and a travel trade journal, which used it to illustrate a report on how tourism can disrupt host societies. From there it was picked up again by Time magazine and published as part of a cover story on the Asian tourism boom, and with this, Rajendra found he had finally won the approval of his family.

"I couldn't care less about an establishment journal like Time magazine," he said. "But my family was really proud of me. They'd never taken my writing seriously before."

Now they are more willing to consider his point of view, though his mother still wishes he would stop courting disaster with his foolhardy criticism of the rich and powerful.

"This time you've gone too far," she tells him each time a new controversy blows up, usually as a result of his columns in The Star.

"I try to explore the real values of Asian society, the cultural and spiritual values, not just the material values, which is the way the whole development process here is going," says Rajendra.

Cultural corruption

They come back corrupted, aping Western styles of 20 years ago. Our writers and poets are obsessed with empty form and the lofty ideals of 'art for art's sake', to the total exclusion of social relevance."

"The only alternative is silence, which is no alternative at all."

-- Photograph Christine Thery

Social relevance is his constant theme, and it has made him plenty of enemies. Though pertinent, his scathing attacks on the artistic and literary establishment have not exactly helped to placate them. Late last year, establishment resentment came to a head when he wrote a stinging reply in The Star to an extraordinary criticism of his work by Ooi Boo Eng, Professor of English at the University of Malaya. Rajendra, Ooi has written, was not a "true artist".

"The man has talent, which he has so far squandered. He isn't anywhere near being the poet he could have been had he been as consistently exercised by the ideal of poetry as agonizing if also joyous creation and arduous or even fastidious craft as much as he has been concerned with poetry as 'sincere', 'committed' statement in the cause of social and humanitarian issues."

"Ever tried stopping a tank with a neatly crafted stanza?" Rajendra demanded. "Or filling a child's belly with an over-ripe metaphor?"

He was hardly prepared for the widespread outrage this drew. He did receive support, but it was all but swamped by a tsunami of abuse and vituperation.

"Some of the letters really shocked me," he said. "A couple of them were definitely actionable, and some were from people I had thought were my friends."

He gave as good as he got in the following weeks as the controversy raged, but he was not sorry when the Asian PEN Conference held in Manila in December provided an escape.

"It started to erode my confidence," he admitted. "It was a great relief to be with people in Manila who see things the same way I do, writers who are committed to the same things."

Yet the conference wasn't much better.

"The theme was supposed to be 'Literature and Social Justice', but there were a lot of people there who took no notice of that: it kept degenerating into a sort of marketing seminar on the difficulties of getting your book published."

Writer's duty

"It becomes no longer a matter of choice, but the moral obligation and bounden duty of every responsible writer to bear witness to the times he lives in and to put his life and his work at the service of humanity."

His speech, brief and to the point, was widely reported in the Philippines press and elsewhere in the region, but virtually ignored in Malaysia.

At the conference the debate raged to and fro, ending with a points victory for Rajendra and other committed writers like Mochtar Lubis, the award-winning Indonesian journalist, who delivered a powerful keynote address on injustice, and constantly strove to steer the erratic and confused discussion back onto its theme.

For social commitment does not come easily to East Asian writers. There is virtually no tradition of criticism in their countries, no real debate between rulers and ruled, no middle ground between meek acceptance and outright rebellion. Politics has always been and still is the politics of the elite.

Within the elite, criticism is a ploy, a gambit in a power play. Criticism such as Rajendra's, based on public accountability and unlinked to a bid for personal gain, is seldom understood or accepted, seldom suffered lightly.

It is a dangerous game. Even Rajendra's enemies admit he is not short of courage, but in the end that may not be enough. Some of the Draconian measures he lampoons in "Animal & Insect Act" could easily cost people like Rajendra their freedom.

"My position in Malaysia is very tenuous," he admits. "But the only alternative is silence, which is no alternative at all."

"It becomes no longer a matter of choice, but the moral

obligation and bounden duty of every responsible writer

to bear witness to the times he lives in and to

put his life and his work at the service of humanity."

Meanwhile, there are plans to publish a collection of his critical essays from The Star and elsewhere, and his sixth volume of poetry has gone to the publishers. The title poem is "Hour of Assassins", dedicated to the memory of Dr Walter Rodney, Third World historian and political activist and Rajendra's friend, murdered in his native Guyana.

The book is to be published by Bogle-L'Ouverture, a firm founded by Rodney's long-time friend Jessica Huntley specifically to publish Rodney's books, and now a leading Third World publisher.

"Jessica wanted to publish 'Bones & Feathers', but, like a fool, 1 wanted it published here," Rajendra said. "Though I don't regret it -- I've done what I can here as far as local publishers are concerned, but I haven't had much joy with them. Probably more people will read my books if they're published abroad."

Each of his books has been better than the last, and "Hour of Assassins" is no exception. Rajendra's earlier work, including many of the poems in "Bones & Feathers", was written for live performance with his Third World Troubadours, which he formed in 1972 with musicians Cecil Roberts of Sierra Leone and Helio Diaz Pinto of Brazil.

The group, which had sprung from the Black Voices Forum Rajendra had started in London's old Troubadour folk club, toured Britain, Europe and North America for the next three years until Rajendra returned to Penang.

Silence of print

Some of the poems from this period, shorn of their vibrant Afro-Brazilian backing and reduced to the silence of print in book, lost something in the process, while others, written more recently, seemed a bit unsure of themselves. Rajendra himself says in retrospect that he has doubts about some of the poems in "Bones & Feathers". "Some of them should not have been published at all."

It is not that he rushes into print. He often spends years crafting a poem, belying their freshness and immediacy, and fully 80 per cent of what he writes is never published. It is simply that he has been maturing steadily.

"Refugees & Other Despairs" was a definite improvement, stronger and less patchy, but still transitional compared to "Hour of Assassins". Though he regularly reads his poems in public, at meetings, in schools and even factories, his major audience now consists of readers, not listeners, and his work has come to terms with this.

The new book achieves a full transition, without loss. Now the beat is fused into the written words, the assonance and dissonance are part of the rhythmic structure, giving the flow of word and their meanings powerful emotional undertow:

When small liberties

began to fray...

When their constitution

was being chipped away

When their newspapers

were shut down

When their rule of law

was twisted round

When might became right

and their friends

were carried off screaming

in the pitch of night...

They chose silence

feigned blindness

pleaded ignorance.

And now when the shadow

of the jackboot hangs

ominous over their beloved land

they walk as zombies

unable to distinguish right from

wrong from right

their minds furred with lichens

like the dark side of trees.

These poems are vintage Rajendra. Like his earlier work, they will travel well, and are bound to turn up in the most odd places.

POETRY:

Strength underpinned with skill

by Keith Addison

Published in Far Eastern Economic Review, June 23 1983, and Sunday Star, Malaysia, June 26 1983

Hour of Assassins by Cecil Rajendra. Bogle-L'Ouverture Publications, London. £2.95 (US$4.50).

CECIL Rajendra is Malaysia's best-known poet, but he is much more than that: he is a one-man pressure group, committed to awakening people to the social evils that beset his country and the world in general. His poems have been internationally acclaimed, but in Malaysia he is a highly controversial figure with as many detractors as admirers, and this book -- his sixth and his best so far -- will probably win him as much vilification as praise there.

It is difficult to be indifferent to Rajendra: his vitality ensures a response of one kind or the other, and in this book the familiar strength is underpinned by a more deft skill with words, and a deadlier aim for his barbs, than can be found in his previous anthologies (Bones & Feathers, 1978, and Refugees & Other Despairs, 1981). The sacred cows, pompous myths and hypocrisies of established power emerge mauled, exposed, discredited, deflated, ridiculed or lampooned.

Local establishment apologists will no doubt take the bait, and respond as shrilly as they have done in the past. For instance, his legal peers (Rajendra is a lawyer and runs a practise in Penang) will not relish the distinction he draws in poems like Proper Attire between justice and the legal rigmarole with its "paper-shifting inanities".

The local literary establishment, staunchly formalist, has reviled Rajendra's work on account of its social commitment, which is seen as a "pollution of literature" and "artistically gross," but Rajendra has paid no heed to these admonishments: the latest volume has more social content than ever, as well as a biting parody of the whole detached "art-for-art's-sake'' approach in Instructions to True Poets: "You must concentrate on precious things like love & loneliness; you must steer clear of obnoxious cliches like blood & dying children."

Religious establishments, whether Islamic or Christian, also come under attack. There are poems about the plight of rubber tappers, dispossessed farmers, fishermen "developed" off their beaches, the homeless, the hungry, the politicians who change their tune once they are in power; businessmen who cash in on other people's heritages; all the modern madnesses of war, the arms race, ecological ruin -- it is all there, cuttingly and movingly.

But Hour of Assassins is more than a catalogue of evils; much of it is also fine poetry. Rajendra's art has developed steadily through the years, and though he is still inconsistent, in many of these poems he succeeds in taking his readers (those of them he does not antagonise!) with him, through subtle rhythms in the written words that complement the subject matter and cut the dross from the images.

The title poem echoes Rajendra's grief at the murder of his friend Walter Rodney, author of the classic How Europe Under-developed Africa: "And now I cannot sleep, but turn over and over those too brief moments we ground together, clasped hands across three Continents, straightened the past, mapped our visions, exchanged those dreams …" He despairs at "the asafoetida memories of a lifetime of lives truncated in full flower". But there is also his Song of Hope, a litany against despair.

And, as well as the diamonds studding the ripened fingers of chauffeur-driven "mems" pinching a brinjal at a market stall, set against the tears of a refugee child, or the awful sameness of modern suburbia's "photo-copy lives", there are poems about ordinary yet magical children, trees and the evening wind, rainbows in puddles of oil-slicked water, about love -- in fact, about all the "precious little things" he lampoons in Instructions to 'true' poets.

Rajendra is a true poet. "It becomes no longer a matter of choice, but the moral obligation and bounden duty of every responsible writer to bear witness to the times he lives in and to put his life and his work at the service of humanity," he said in his address at the Asian PEN Conference in Manila. Why do so few have the courage?

Books by Cecil Rajendra

Bones and Feathers, 1978, Heinemann (Writing in Asia), Hong Kong, ISBN 0686603338

Refugees & Other Despairs, 1980, Choice Books, Singapore

Hour of Assassins, 1983, Bogle-L'Ouverture Publications, London, ISBN 0 904521 29 X

Songs for the Unsung... Poems on Unpoetic Issues like War and Want, and Refugees, 1983, World Council of Churches, Geneva, No. 19 in the Risk Books series, ISBN 2-8254-0785-2

Child of the Sun, 1986, Bogle-L'Ouverture Publications, London, ISBN 904-521-37-0

Dove on Fire: Poems on Peace, Justice and Ecology, 1986, World Council of Churches, Geneva, ISBN 2-8254-0899-9

Lovers, Lunatics & Lalang, 1989, Bogle-L'Ouverture Publications, London, ISBN 0 904 521 47 8

Broken Buds, 1994, The Other India Press, Goa, India, ISBN 81-85569-08-8