by Keith Addison

Published in Asian Business, March 1983

|

Stories by Keith Addison |

| Tai Long Wan -- Tales from a vanishing village Introduction |

|

Tea money |

|

Back to basics |

|

Forbidden fruit |

|

A place where nothing happens |

|

No sugar |

|

Treasure in a bowl of porridge |

|

Hong Kong and Southeast Asia -- Journalist follows his nose |

| Nutrient Starved Soils Lead To Nutrient Starved People |

|

Cecil Rajendra A Third World Poet and His Works |

|

Leave the farmers alone Book review of "Indigenous Agricultural Revolution -- Ecology and Food Production in West Africa", by Paul Richards |

|

A timeless art Some of the finest objects ever made |

|

Health hazards dog progress in electronics sector The dark side of electronics -- what happens to the health of workers on the production line |

|

Mo man tai ('No problem') -- "Write whatever you like" -- a weekly column in Hong Kong Life magazine Oct. 1994-Jan. 1996 |

|

Swag bag Death of a Toyota |

|

Zebra Crossing -- On the wrong side of South Africa's racial divide.

|

|

Curriculum Vitae |

|

|

A Swiss horologist is visiting Hong Kong with some of the finest objects ever made. Keith Addison reports

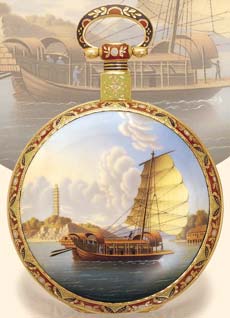

Each part a work of art: an 11-jewel gold watch made for the Chinese market by Edouard Juvet, Fleurier, circa 1840 -- the quintessence of European engineering, mathematics and chemistry, and the craft of the goldsmith, of the engraver, the chaser, the jeweller, the enamel painter. Only the Chinese could afford such a watch. |

Since all matters pertaining to the calendar and the measurement of time were the traditional prerogative of the Court of Heaven to order and change by decree, the clockmaker presented his wondrous machine to the Emperor.

This master engineer, in typical Chinese style, kept his methods a close family secret, teaching the art of making clocks only to his son, who in turn taught it only to his son, with all clocks made by the family entering the Emperor's collection.

But then there was a family tragedy and the clockmaker's line died out -- and the secret of clockmaking with it.

Further tragedy followed: a hundred years later the capital was moved south under pressure from invading hordes, and the entire collection of clocks was lost in the move.

But such a potentially useful instrument could not stay lost forever, and though the Sung dynasty clocks were never found, the secret of making mechanical clocks was rediscovered within a hundred years, in Europe.

Like their Chinese precursors, the first European clocks were little more than curiosities, one sign among many of rapidly developing technological capabilities, but the inexorable unfolding of European history ensured that their makers' art would not end up languishing in some mediæval prince's bric-a-brackery.

Steadily mounting social, commercial, economic and political pressures saw Europe burgeoning out into the high seas in search of discovery, foreign trade and conquest.

Hundreds of years earlier, Chinese sailors had relied on their seamanship, their instincts and good fortune in pushing their trade through the Indian Ocean, eventually exploring Africa and even the west coast of the Americas. But the European expansion set a premium on any developments which might aid the new science of navigation.

Cartography blossomed. Portugal's Prince Henry the Navigator (who never left Portugal) invented the magnetic compass, and it was soon realised what an aid to navigation an accurate clock would be. German bankers, appreciating how important navigation was becoming to commerce, offered clockmakers large cash sponsorships to help them in their efforts to achieve greater accuracy and reliability in their instruments.

When a group of Jesuit priests visited the Court of Heaven in Peking in the mid-16th century, though they had faced many perils on their voyage, they had not sailed on uncharted seas, having followed the westward route to the east begun by Columbus and completed by Ferdinand Magellan.

As a token of respect and in recognition of the Emperor's traditional sway over the ordering of Time's progress, the Jesuits presented the Celestial Court with a collection of the finest European watches.

As a token of respect and in recognition of the Emperor's traditional sway over the ordering of Time's progress, the Jesuits presented the Celestial Court with a collection of the finest European watches.These were a well-chosen gift: European watches were by then the finest and most advanced examples of precision engineering of the time, their workings fantastically miniaturised; more than this, they had passed into the realm of high art, and now incorporated the best examples of the jeweller's, the goldsmith's and the engraver's crafts, as well as those of the engineer and the mathematician-designer. The Emperor was extremely impressed.

Ownership of a fine European watch soon became China's ultimate status symbol, the token of a patron of science and the arts, a talisman of power and a sign of great wealth, for such watches were very expensive.

Fine watchmakers in Geneva, London and Paris quickly realised this. The steadily improving quality of their best work was already beginning to price them out of their home markets, with the number of Europeans who could afford a state-of-the-art watch steadily dwindling.

In China, though, wealthy mandarins, when offered the very best watches, did not quibble about the price. European horologers began making watches specially for the new Chinese market, and it proved their mainstay for 250 years, the only market rich enough to support their strivings towards the perfection of their art.

Master Swiss watchmaker Edouard Bovet was one of the many who concentrated on the Chinese market. He arrived in Canton in 1830 carrying five top-quality watches, all of which he sold immediately, to mandarins who paid him in gold bars.

Delighted, he wrote to his brother in Switzerland, enthusing about the market potential and asking him to send more watches, but only of the very best quality, since this was where the demand lay and there was no difficulty about payment.

The 17th century Ching Dynasty Emperor K'ang-Hsi was a great admirer of the European sciences, especially that of horology, and he established several imperial workshops in which Chinese craftsmen made clocks and watches under the direction of imported European watchmakers, amongst whom were several masters. At K'ang-Hsi's invitation, the Zougeese master watchmaker François-Louis Stadlin became director of the imperial workshops, and the Emperor's favourite.

Stadlin died in Peking in 1740 at the age of 82; his grave was rediscovered in 1942. Despite his efforts, and though fine watches were made in China, the workshops did not flourish. It is no simple matter to transplant an industry from one continent, where it has been developing for hundreds of years, to another where there is no such tradition. China, though she had been the first in the field, failed to re-establish the watchmaker's art. The finest watches continued to be made in Europe -- and sold in China.

Osvaldo Patrizzi |

Often they have travelled far. Osvaldo Patrizzi, a horological historian and one of the foremost dealers in antique watches, travels on average 25,000 miles each month in search of these treasures, and he finds them all over the world.

"They are small, and very precious," he says, "the ideal nest-egg to take when people move to a new country. Some of them have changed owners many times, yet they are still in perfect condition."

He sees the care taken of them by successions of owners, sometimes through hundreds of years, as betokening more than a knowledge of their cash or investment value alone, or even of their superb craftsmanship and their artistic value. He takes the horological historian's point of view, in which human progress is charted according to improving abilities to measure time.

"Watches such as these are important documents of human evolution," he says, and he believes their owners have appreciated this in some way.

|

|

|

|

|

"There is also a romantic aspect to it: people form very strong attachments to their watches, similar to those they form with other people. A man's watch can be his constant and trusted companion for 40 or 50 years. In some ways a watch is almost a living object in itself."

This proxy life has long been recognised in lore such as the old song about the grandfather clock which "stopped, never to run again" the second the old man died, and in the common claim that a watch, otherwise accurate, loses time when its owner falls ill.

Patrizzi produced an old watch which was definitely a romantic object.

"This watch was made in Germany in about 1560. It is 420 years old. Can you imagine what Germany was like then? Or China? What it has seen, this watch! The passing history it has measured, hour by hour, the people who have owned it, and loved it..."

The watch, a round disc two inches across and not quite one inch thick, in an entirely and minutely chaste gilt casing, was certainly beautiful, and after four centuries it still told the time. But apart from this dynamic aspect, could it possibly have some enigmatic life of its own, gleaned by some form of osmosis from the procession of lives with which it had been so closely intertwined? Holding it, it wasn't hard to believe. Nor was its "life" over yet: via Patrizzi it was destined to find a new owner, who would no doubt find many hours of contemplation in it -- a fine focus for the imagination, with a heart that beats.

Most of these watches have this almost-magical aura, perhaps born in the alchemy wrought upon them by their makers in the many hours of painstaking craftsmanship of such a high order.

Made for China in 1830 by Bovet of London |

He opened the casing, revealing a magnificent movement, the metal surfaces gleaming like mirrors.

"The movement is made of the best quality steel, each part is highly polished to resist rust -- specially made for the climatic conditions of China. It chimes on demand, sounding the hour and the quarters."

He demonstrated, and the watch sounded 10 clear chimes, followed by a double tone for a quarter: 10.15.

"This watch is a work of perfection. There is so much here: the fantastic engineering, as well as the work of the goldsmith, the engraver, the chaser, the jeweller (the pearls are perfectly graded), the enamel painter.

"Enamel painting especially is very difficult: this central medallion, the lake landscape, is a perfect miniature, painted with a single frond from a feather. The painter also had to be an expert chemist: the enamel is baked at 820ºC, which changes and fades the colours. Each painter had his own secret formulæ for mixing the paints to achieve the desired effect. This is a work of very great skill."

In fact, though the various motifs were Chinese in origin, the style in which they had been rendered was strongly and ornately European: one would have to be told the design was intended to conform to Chinese tastes.

Yet there was no failure in this: while too European for conventional Chinese tastes, and too ornate for those who find beauty in simplicity, the extraordinary quality of the workmanship soon transcends questions of individual taste, evoking nothing but admiration.

"It is in perfect condition, it works perfectly. After 170 years there is not a scratch on it. Of course it was made from the best materials available, often special materials developed after a lot of research. What is it worth? About HK$400,000."

Another watch: "This is a superb watch, again typical of those made for China. This one was made in 1803 by William Ilbery of London, who developed a special calibre of quality watch for the Chinese market."

Again, incredible craftsmanship and attention to detail, and on the back, a magnificent painted medallion, two inches in diameter, of a marine life scene: small boats and fishermen at a rocky shore, a fort, distant hills, galleons at anchor, and a superb sense of depth arising from an almost translucent golden mist shrouding the distant perspective.

"This painting is absolutely fantastic," said Patrizzi, lost in admiration, and obviously not for the first time. "Fabulous..."

He opened the watch: "The movement is superbly designed and built, finely decorated; the main bearing, here, is a diamond, proof against wear; there are also seven sapphires. The whole movement is protected by this special dustproof cover.

"This watch is a unique work of art. It is worth between HK$400,000 and HK$600,000."

Probably made by Bovet in Fleurier for the Chinese market circa 1840 |

Some were a good deal less sober, dubbed "curious" rather than "rare and beautiful" in Patrizzi's catalogue, with "libertine automatons" -- animated pictures made in sections which moved, driven by the clockwork mechanism. One such featured a "libertine scene with two personages" lustily engaged in that human activity most seldom measured by clocks; in another an automated couple coupled while a male friend, explicitly and enormously equipped, stood by, awaiting his turn.

Also included were a watch made in China by Stadlin, two 19th century Japanese clocks, complete with netsuke, and a 19th century Chinese "fire alarm clock", shaped like a dragon boat on wheels, the hull bearing a graduated metal trough containing a mixture of argil, Tibetan wood-dust, musk and gold dust; this was set alight and smouldered steadily, showing by its position how much time had elapsed. Two balls joined by a silk thread could be positioned over the trough so that the thread would be burned through at the appointed time, allowing the balls to drop onto a steel plate, sounding the alarm.

Neither were all the timepieces particularly rare, nor even expensive: "We have a section devoted to fine wristwatches, not particularly old, made in the last 70 years, but now out of production. We have found that this section has created great interest amongst younger people who are neither watch collectors nor millionaires. Most of today's watches look much the same, unless you are going to spend a great deal of money. These older watches offer some individuality and they are not expensive -- often they are cheaper than many new watches. They are all excellent watches made by the best watchmakers -- Rolex, Vacheron & Constantin, Patek-Philippe -- and they keep perfect time.

"Watchmaking achieved a peak of technical perfection at about the beginning of this century; any watch made by good makers since then will be a superb instrument, well worth owning.

"Now, of course, with the advent of the electronic watch, the centuries of development in mechanical watchmaking have drawn to a close. There is no more future for mechanical watches, excepting as antiques. This is a logical development, but yes, in a way it is a pity. Yet the story continues: the first electronic watches, made in 1947, are now valued collectors' items, and very rare, for they too are documents of human evolution.

"We have noticed in the last 10 or 15 years that collectors are becoming very professional, extremely knowledgeable. There is now an excellent literature of 400-500 books on the subject, covering the lives of the master watchmakers and many aspects of their art, including such associated subjects as enamel painting. The interest is mainly historical, and this is a fascinating point of view from which to study history. From the point of view of art collection, this gives fine watches a meaning and a dynamic aspect, and an opportunity for involvement, that fine paintings simply do not have.

"So many great men have collected watches in the past: Charlemagne, Napoleon -- many of the great figures, and most great men of science.

"Today there are many collectors: there are 40,000 members of the antique watch association in the US; more than 10,000 in Europe; more than 3,000 in Britain, and a rapidly growing number in East Asia. In Hong Kong there are now many collectors: Li Ka-shing and Michael Sandberg, for instance, both have good collections. Many less well-known people, with much less money, are also collectors.

"The market is constantly developing: there is no danger that all the best pieces will become locked up in museums or other stable collections, causing market stagnation. Many of our clients are investors as well as collectors, and this ensures that good pieces will always be available.

"As for their investment value, I will give an example: in 1954, King Farouk's collection of 89 antique watches was sold in Cairo for a total of £110,000; I recently sold one of those watches, and not the best one in the collection, for more than £110,000. Of course this is not always the case, it is very difficult to find an accurate average. The best advice is to buy the best quality you can afford. The better the quality, the greater the likelihood that the value will increase significantly."

Antiquorum's Hong Kong sale has become a major event in the watch collector's calendar. Patrizzi also holds annual auctions in Geneva and New York, but the best pieces are reserved for the Hong Kong auction, and buyers from all over the world attend.

This year the 150 items he offered fetched a total of HK$6.5 million, some pieces being knocked down for twice the expected price.

The German watch made in 1560 sold for HK$200,000; the magnificent Piquet & Meylan of 1815 sold for the expected sum of HK$400,000; the William Ilbery of 1803 sold for HK$580,000. Each watch was sold with a certificate of guaranteed authenticity which Antiquorum is unique in providing, possibly because Patrizzi is himself an authority and can supply authentication without greatly increasing his costs by seeking outside expertise.

His own wristwatch is not an antique: he wears a solid, black-faced Rolex sportsman's watch covered with function dials.

"I am a scuba diver, and this watch is very useful to me," he explained. "But I love my watch: it was given to me by an ex-president of Rolex, after I had provided expertise for the Rolex collection."

-- Asian Business March 1983